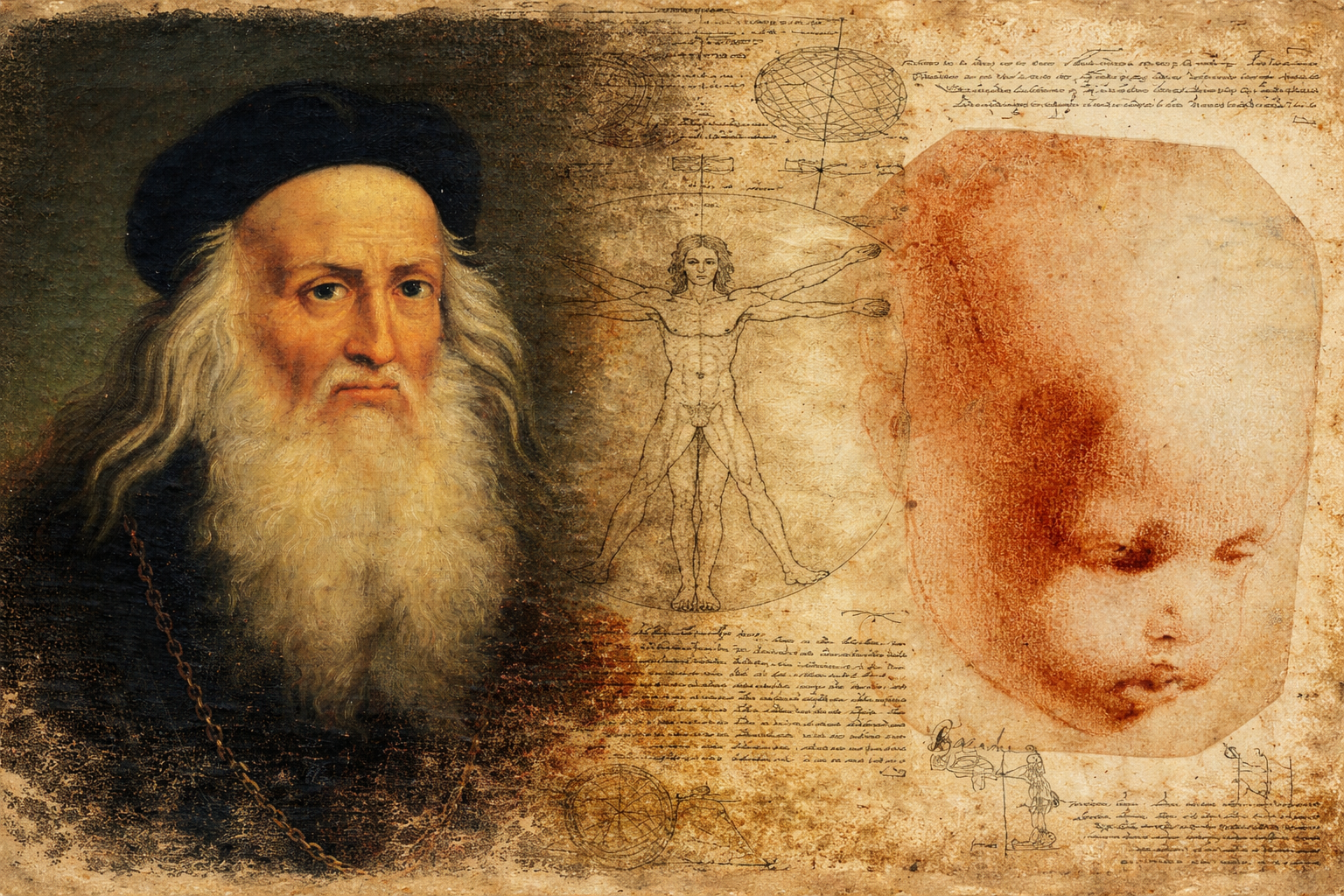

In the quiet, temperature-controlled storage vaults of the Royal Library of Turin, a drawing is kept in the dark. Art historians say that this is a study in red chalk of a baby’s face, called the “Holy Child,” which is thought to have been made by Leonardo da Vinci. It is a great example of sfumato, where lines fade into shadow, showing how quickly an expression can change. But to a new type of researcher, this piece of paper is more than just a piece of paper. It’s a crime scene, a biological archive, and a Petri dish that has been sitting around for five hundred years. It is a crowded, hidden city of DNA, proteins, and microbes that holds secrets that can never be seen.

There is a quiet revolution happening in the study of the Renaissance. It is moving the field from the subjective “connoisseurial eye” to the hard, measurable world of the molecular sequencer. This field, awkwardly called “arteomics,” says that a work of art is not just a surface for paint; it is also a trap for biological history. There is a mark on it from every hand that has touched it, every cough that has sprayed it, every fly that has landed on it, and every animal that has been boiled down to make its glue. As we peel back these layers, we see that the Renaissance was more than just a time of artistic awakening; it was also a biological event that is still present in the chemistry of its greatest works.

A Genomic Picture of the Renaissance Master

As expected, the search for the biological Renaissance began with its most mysterious person: Leonardo da Vinci. For hundreds of years, historians have searched through archives for bits of his handwriting. Now, the Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project (LDVP) is searching through his art for bits of his skin. The project’s goal is almost too big to be true: to find the artist’s genome in the marks he left behind when he mixed paint with his fingers or smudged chalk.

The drawing of the “Holy Child” became the main focus of this investigation. Researchers used a special, non-invasive swabbing method that was like a gentle forensic dusting to remove debris that had built up over hundreds of years from the paper’s fibers. The genetic soup that came out was a messy mix of bacteria, fungi, and human DNA. But a signal came through this biological noise. The researchers found a Y-chromosome haplogroup called E1b1b. This lineage has deep roots in North Africa and the Mediterranean, which fits with the population of Tuscany during the Renaissance.

This discovery does not conclusively establish Leonardo’s authorship; the drawing has traversed numerous collectors, framers, and curators, any of whom might have inadvertently removed the necessary cells. Still, the fact that this lineage is the same as the one found in the remains of people who lived at the same time as Leonardo gives us a probabilistic anchor. It indicates that the biological provenance of the object corresponds with its art-historical classification.

The environmental DNA recovered from the drawing may have been more evocative than the human DNA. The sequencer found the genetic signature of Citrus spp., which are sweet orange trees. In the Renaissance, oranges weren’t the common fruit they are now. They were expensive, high-status fruits grown in the private limonaia of the wealthy elite, like the Medici family in Florence. This botanical DNA takes us back to the exact sensory environment in which the artwork was made. We can picture the artist’s hand moving across the page as the sheet of paper sat on a table in a sunlit loggia. The air was thick with the smell of citrus blossoms from the Medici gardens. The biology supports the history, anchoring the intangible image in the real soil of Renaissance Tuscany.

The Bacterial Geography of Renaissance Art

If looking for Leonardo’s DNA is like looking for a needle in a haystack, studying the Renaissance microbiome is like looking at the haystack itself. Researchers found that seven Leonardo drawings have a “core microbiome,” which is a unique community of bacteria and fungi that have settled on the paper over hundreds of years.

For a long time, conservators thought that fungi were the main threat to paper. This study, however, showed that bacteria are much more dangerous. Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes were the most common microbes. These tough organisms can break down the cellulose in the paper and the collagen in the sizing. These organisms aren’t just dirt; they’re the “dark matter” of the art object, a living layer that has grown with the drawing.

This microbial life is very important because it can track where things are. Researchers found different biological fingerprints when they compared drawings kept in the Royal Library of Turin to those kept in the Corsinian Library in Rome. The drawings from Turin had a microbial signature that showed the cooler, continental climate of Northern Italy. The drawings from Rome had a biological mark that showed the humid Mediterranean climate.

This “biocodicology” says that a drawing from the Renaissance is a passive record of its travels. It takes in the airborne microbes from the cities it lives in, making a biological passport that shows where it came from. A drawing that spent a hundred years in a damp Venetian palazzo will have a different microbial load than one that spent the same amount of time in a dry Spanish monastery. For the art historian, this is a new way to tell if a work of art is real: if a “lost” Leonardo has a microbiome that talks about 20th-century New York instead of 16th-century Milan, the biological difference is a red flag. The “human contamination” on these works, which includes bacteria from the skin and saliva, is no longer trash to be thrown away. It is now a record of the object’s social life, a molecular memory of every gaze and touch it has received.

The Renaissance’s Molecular Kitchen

Genomics tells us who and where, while proteomics, the study of proteins, tells us how. For decades, art history books have told a simple story about Renaissance painting: the Italians used egg tempera (brittle, fast-drying, matte), and the Flemish invented oil painting (lustrous, slow-drying, versatile), which the Italians later used. Paleoproteomics has shattered this simplistic dichotomy, demonstrating that the Old Masters were not merely artists but empirical chemists who developed advanced hybrid materials.

Take Sandro Botticelli, who is the best example of a painter from the Florentine Early Renaissance. People used to think that his paintings, like The Birth of Venus, were made with only egg tempera. However, a recent proteomic study of paintings from his workshop has found tempera grassa, which is a planned mixture of egg yolk and oil. This was not a mistake. Botticelli and his helpers knew that adding oil to the yolk made it take longer to dry and made the colors blend better. This made the transition from the graphic linearity of tempera to the tonal depth of oil. The proteins show us that the “technological disruption” of oil paint didn’t happen all at once; it was a slow, experimental process in the traditional Renaissance workshop.

With the Venetian masters, things get even more complicated. Titian, a giant of the High Renaissance, was known for his thick, shiny oil glazes. But proteomic analysis of his works, including those in the Poesie series, has found egg proteins mixed into the final layers of varnish and glaze. Why would an oil painter go back to using egg? The molecular evidence indicates that Titian employed the protein to produce particular optical effects, potentially to alter the surface’s sheen or to establish a barrier between layers. This “molecular gastronomy” of the Renaissance studio shows a level of technical detail that the naked eye could never see.

Even Raphael, the epitome of High Renaissance excellence, has undergone this molecular scrutiny. An examination of his Ansidei Madonna showed that walnut oil was used as a binder. Linseed oil turns yellow as it gets older, but walnut oil dries clear and keeps the color of the pigments. Raphael’s choice was a deliberate chemical one to keep the brightness of his blues and skin tones, which shows how much he cared about the longevity of his art. We no longer see the Renaissance artist as a divinely inspired genius painting a canvas. Instead, we see them as a practical craftsman who knows a lot about lipids and amino acids.

Resurrection and the Extinction of the Renaissance

The biological records from the Renaissance include more than just humans and microbes; they also include animals. This gives us a look at a biodiversity that is no longer present. Researchers used mitochondrial DNA analysis in a surprising way to look at the animal glues that Donatello, a great sculptor from the 15th century, used.

Artists and sculptors used glue made from boiling down animal connective tissues like hides, bones, and hooves to hold pigments together or seal surfaces. Scientists thought they would find the genetic signature of common domestic cattle (Bos taurus) when they looked at the collagen in the polychromy of Donatello’s Madonna of Citerna. Instead, one sample had a DNA sequence that belonged to the Aurochs (Bos primigenius).

The aurochs was a huge, wild animal that lived in Europe’s forests until it died out in 1627. It was the ancestor of modern cattle. The presence of Aurochs DNA in a 15th-century sculpture demonstrates that these animals were still being hunted or possibly managed alongside domestic herds in Renaissance Italy. Donatello’s sculpture is not just a piece of art; it is also a biological specimen, a reliquary that keeps the genetic code of a species that is no longer alive. It reminds us that the world of the Renaissance was wilder and had more different kinds of plants and animals than our own. In that world, artists got their materials straight from nature, which had not yet been fully tamed.

In contrast, proteomic analysis of medieval paint from the Uvdal Stave Church in Norway found not only the expected milk casein binder but also a lot of human saliva proteins. The artist did not include this as part of a ritual; it was probably caused by modern contamination, like restorers licking their brushes or visitors talking too close to the artwork. It is a warning: the bio-archive is a palimpsest. To comprehend the Renaissance, we must penetrate the biological noise of contemporary times, differentiating the ancient Aurochs from the modern spit.

The Forensic Renaissance: Realness in the Age of Biology

The stakes of this research go far beyond academic interest; they reach into the multi-billion dollar throat of the art market. Forgery is a dark part of the Renaissance, and traditional ways of checking the authenticity of art, like provenance research and stylistic analysis, have not been able to stop high-quality fakes. But it’s harder to lie to biology.

Wolfgang Beltracchi, the most famous forger of the 21st century, shows how easy it is for experts to be fooled. Beltracchi tricked everyone by painting on old canvases and using frames that were appropriate for the time, which let him get around normal dating methods. But in the end, a chemical anachronism (Titanium White) caught him. The “Bomb Peak” will be a much tougher opponent for forgers in the future.

In the middle of the 20th century, testing nuclear weapons added twice as much carbon-14 to the air. There is “bomb carbon” in every living thing that has been organic since 1955. Scientists can now tell if the flax plants used to make the oil were picked before or after the atomic age by looking at the lipids in the oil binder of a painting. A painting that looks like a Renaissance masterpiece but has “bomb carbon” in its binder is definitely not real. It is a biological time stamp that can’t be erased by trying to copy the style.

The microbiome also opens up new possibilities for forensic authentication. A real Renaissance painting has a “deep time” microbiome, which is a stable, climax community of bacteria that grow slowly and can survive drying out. These bacteria have been around for hundreds of years. A fake, even one that was baked in an oven to make it crack, will have a “modern” microbiome made up of the fast-growing environmental molds and skin bacteria of the person who made it. Forensic arteomics looks for the “biological signature of time,” which is the opposite of what deepfake detection algorithms do.

The Artist’s Body

In the end, this biological turn brings us back to the artists’ own bodies. The Renaissance’s obsession with fame and individual genius has led to a modern desire to physically reclaim the masters. Researchers found what they think are Caravaggio’s remains in 2010 by matching DNA from a skeleton in Porto Ercole to the last name “Merisi.” The study showed that the artist, who was known for his violent temper and dramatic chiaroscuro, died of sepsis caused by Staphylococcus aureus, probably from a sword wound, and lead poisoning from his own paints. The biology corroborated the biography: his art and his existence were equally deleterious.

Also, Raphael’s exhumation from the Pantheon in 2020 made it possible to make a 3D facial reconstruction from his skull, which confirmed the identity of the remains and how they looked like his self-portraits. These projects are on the verge of a new kind of relic worship, where the “holy bone” of the saint is replaced by the “sequenced genome” of the genius.

We are not just looking at a picture when we look at a Renaissance painting today. We are standing in front of a complicated living thing. The red chalk of the “Holy Child” is not just a drawing; it is a collection of Tuscan dust, Medici citrus, and maybe even the epithelial cells of Leonardo himself. The varnish on a Titian is not just a glaze; it is a record of what the artist ate for dinner. The glue in a Donatello is a tribute to an animal that is no longer alive.

The Renaissance is not a thing of the past. It is alive, full of microbial descendants and preserved proteins, and it is waiting for us to ask the right questions. In the union of art and biology, we discover that the most profound truths of our cultural heritage are inscribed not in ink, but in the imperceptible, enduring code of life itself.

Leave a Reply