Last updated on September 9th, 2024 at 05:07 pm

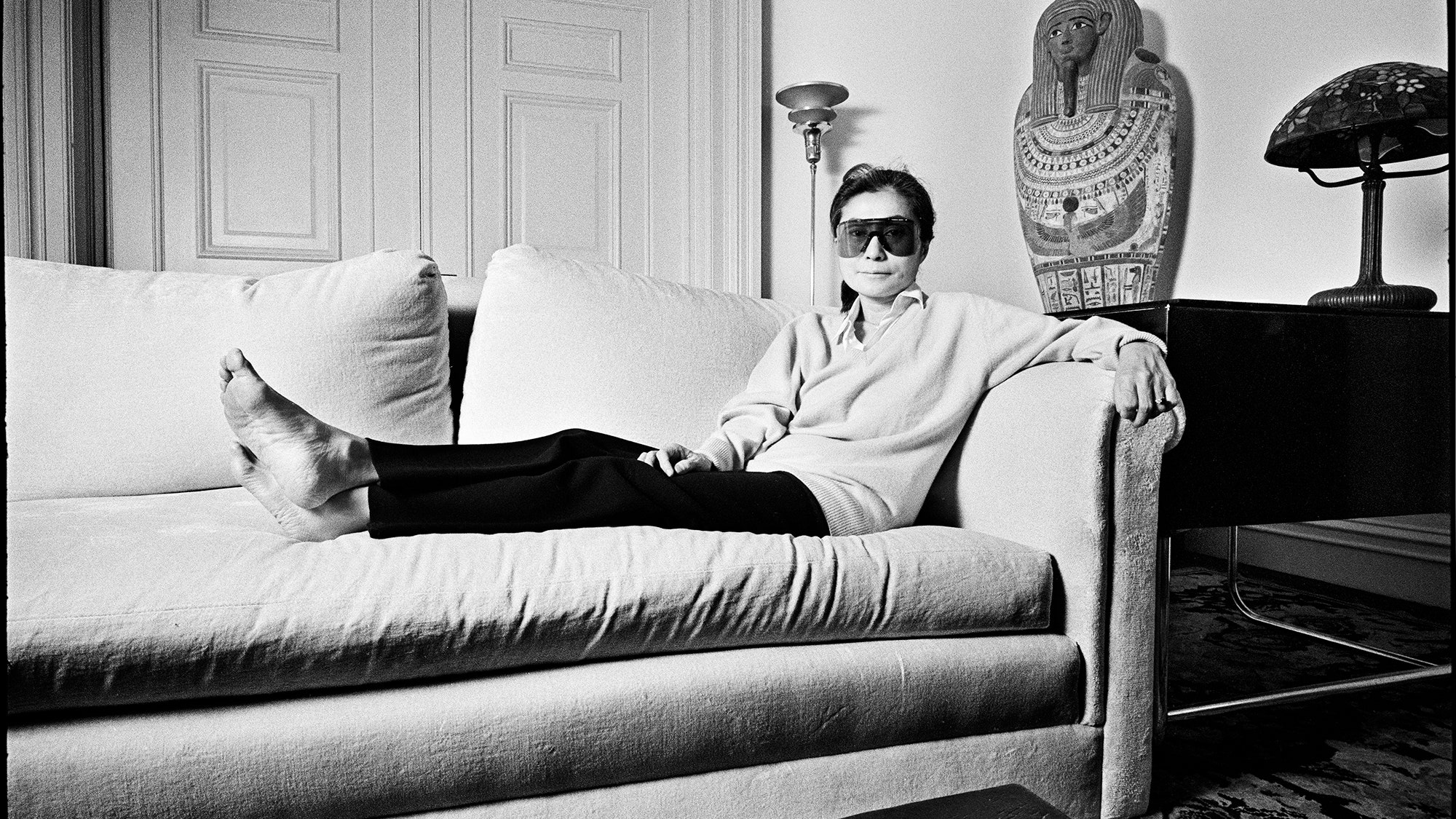

Yoko Ono, a multifaceted artist and activist, has had a profound impact on contemporary art and social activism. Her work spans various media, including visual arts, music, performance, and writing. This article explores Ono’s contributions to the art world, her role in the Fluxus movement, her innovative participatory art projects, and her enduring activism for peace and human rights. By examining her life and work, this paper aims to highlight the significance of Ono’s artistic and activist legacy.

Introduction

Yoko Ono, born in 1933 in Tokyo, Japan, emerged as a pioneering figure in the avant-garde art scene of the 20th century. Often recognized for her marriage to John Lennon, Ono’s own artistic achievements and activism are equally noteworthy. Her work challenges traditional boundaries, encourages audience participation, and addresses pressing social issues. This paper delves into the key aspects of Ono’s career, analyzing her influence on both art and activism.

Early Life and Influences

Childhood and Education

Yoko Ono was born into an affluent family in Tokyo, Japan, on February 18, 1933. Her father, Eisuke Ono, was a banker and a classical pianist, while her mother, Isoko Ono, was an accomplished painter. This artistic environment fostered her early interest in the arts. The family moved frequently due to her father’s job, spending significant time in both Japan and the United States. This bicultural upbringing exposed Ono to a broad range of artistic and cultural experiences.

Ono attended the prestigious Gakushūin School in Tokyo, which was known for educating the Japanese aristocracy. Here, she received a classical education that included traditional Japanese arts and literature. Her exposure to Western culture was further enhanced when her family moved to New York City in 1952, where she enrolled at Sarah Lawrence College. At Sarah Lawrence, Ono studied philosophy and music, which played a crucial role in shaping her avant-garde artistic sensibilities. She was influenced by the works of pioneering composers like John Cage and La Monte Young, whose experimental approaches would later resonate in her own work.

Artistic Influences

Ono’s artistic vision was shaped by a diverse array of influences. Her exposure to traditional Japanese arts, combined with her interest in Western avant-garde movements, created a unique blend of East and West in her work. Zen Buddhism, with its emphasis on simplicity, mindfulness, and the impermanence of life, profoundly influenced her conceptual approach to art. She was also inspired by the Dadaist and Surrealist movements, particularly the works of Marcel Duchamp, whose ready-mades challenged the very definition of art.

John Cage, a leading figure in experimental music, became a significant influence on Ono. Cage’s use of chance operations and his belief that everyday sounds could be music inspired Ono to explore unconventional artistic expressions. Ono’s early works reflect Cage’s impact, blending performance, sound, and visual art in innovative ways.

The Fluxus Movement

Origins and Principles of Fluxus

The Fluxus movement emerged in the early 1960s as a network of international artists who sought to blur the boundaries between art and life. Founded by George Maciunas, Fluxus artists embraced an anti-commercial, anti-art ethos, emphasizing the process of creation over the finished product. They sought to democratize art, making it accessible and participatory. Fluxus events often included performances, happenings, and installations that encouraged audience interaction.

Ono’s Role in Fluxus

Yoko Ono became a central figure in the Fluxus movement, contributing to its development and expansion. She collaborated with other Fluxus artists such as George Maciunas, Nam June Paik, and Joseph Beuys, participating in numerous Fluxus events and exhibitions. Ono’s work epitomized the Fluxus principles, using simple, everyday materials and instructions to create art that was both conceptual and participatory.

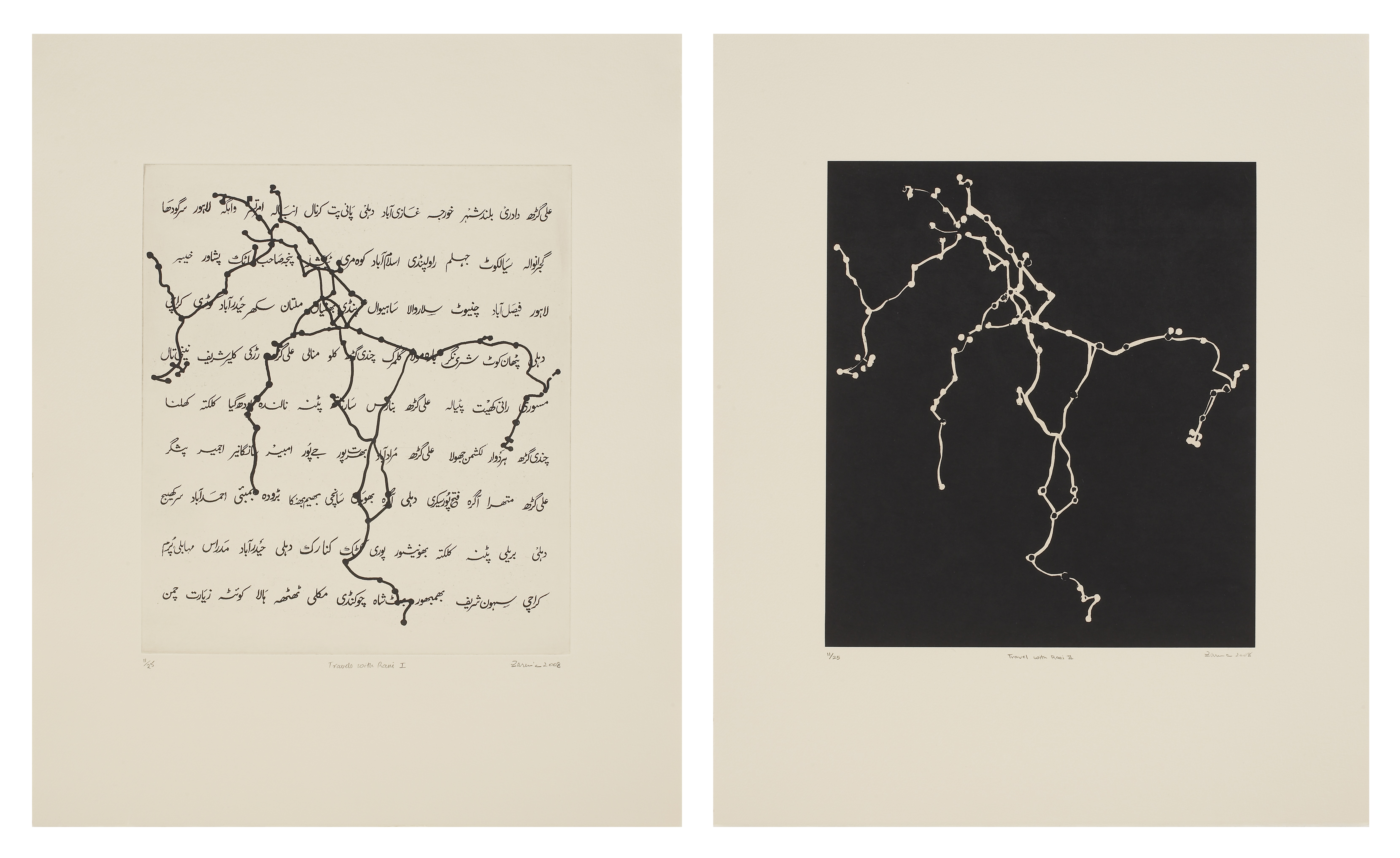

Her “Instruction Paintings” are a quintessential example of Fluxus art. These works consisted of written instructions that invited viewers to complete the artwork through their interpretation and actions. This approach democratized the art-making process, allowing anyone to become an artist by following the instructions. Ono’s “Painting to Be Stepped On” (1960) and “Painting to Hammer a Nail” (1961) exemplify this concept, transforming ordinary actions into artistic experiences.

Instruction Paintings and Conceptual Art

Ono’s “Instruction Paintings” are seminal examples of conceptual art, wherein the idea behind the work is as important as the physical manifestation. These works challenge traditional notions of authorship and art production, emphasizing the role of the viewer in completing the artwork. By providing simple instructions, Ono invited participants to engage with her art on a personal and imaginative level.

One of the most notable “Instruction Paintings” is “Cut Piece” (1964), a performance that involved Ono sitting passively on stage while audience members were invited to cut away pieces of her clothing with scissors. This performance highlighted themes of vulnerability, trust, and the power dynamics between the artist and the audience. “Cut Piece” has been re-enacted several times over the years, each performance offering a unique commentary on societal issues such as violence against women and the objectification of the female body.

Another significant work is “Painting to Hammer a Nail” (1961), which invites participants to hammer a nail into a wooden panel. This simple act transforms the viewer into an active participant, making them complicit in the creation of the artwork. Through these interactive pieces, Ono challenged the passive consumption of art, encouraging audiences to engage directly and meaningfully with her work.

Participatory Art and Audience Engagement

The Concept of Participation

One of Ono’s most significant contributions to contemporary art is her emphasis on participation and engagement. Her work often requires the viewer to take an active role, thereby democratizing the artistic process. By inviting audience interaction, Ono breaks down the barriers between artist and spectator, creating a shared space for creativity and reflection.

The “Wish Tree” Project

The “Wish Tree” project, which began in the 1980s, is one of Ono’s most enduring and popular participatory artworks. This project invites participants to write their wishes on pieces of paper and tie them to a tree. The simplicity of this act belies its profound impact, as each “Wish Tree” installation becomes a repository of collective hopes and dreams.

The “Wish Tree” has been installed in various locations worldwide, from museums and galleries to public parks and urban spaces. Each iteration of the project accumulates thousands of wishes, creating a living testament to human desires and aspirations. Ono’s instruction to participants is simple yet profound: “Write your wish on a piece of paper. Fold it and tie it around a branch of a Wish Tree.” This act transforms personal desires into a shared experience, connecting individuals across different cultures and backgrounds.

Other Participatory Works

Ono’s commitment to participatory art extends beyond the “Wish Tree” project. Her “Play It By Trust” (1966) is a white chess set that invites participants to play a game in which the pieces are indistinguishable from one another. This work challenges the competitive nature of chess, promoting collaboration and trust instead. As the game progresses, players must rely on memory and cooperation, highlighting the importance of mutual understanding.

In “My Mommy Is Beautiful” (2004), Ono invited people to share photos and messages about their mothers. This interactive project celebrates maternal love and encourages participants to reflect on their personal relationships. Through these and other participatory works, Ono creates spaces for communal reflection and engagement, fostering a sense of connection and empathy among participants.

Activism and Peace Initiatives

Ono’s Activism and Philosophical Beliefs

Beyond her artistic endeavors, Yoko Ono is renowned for her activism, particularly in advocating for peace and human rights. Her philosophical beliefs are deeply rooted in the principles of non-violence and social justice, influenced by her experiences during World War II and her exposure to pacifist ideologies.

Ono’s commitment to peace is evident in her numerous campaigns and public statements. She has consistently used her art and public platform to address issues such as war, violence, and human rights abuses. Her activism is characterized by a belief in the power of individuals to effect change, a theme that runs throughout her artistic and activist work.

The “War Is Over! (If You Want It)” Campaign

The “War Is Over! (If You Want It)” campaign, launched in 1969, is one of Ono’s most iconic activist projects. Collaborating with John Lennon, she deployed a simple yet powerful message across major cities worldwide. This campaign utilized the power of media to challenge war and promote peace, encouraging individuals to believe in their capacity to effect change.

The campaign’s slogan, “War Is Over! If You Want It,” was displayed on billboards, posters, and advertisements in major cities such as New York, London, Tokyo, and Rome. This message, combined with the couple’s high-profile visibility, drew significant attention and sparked conversations about the possibility of ending war through collective will. The slogan’s enduring relevance underscores the campaign’s impact and Ono’s visionary approach to activism.

Other Peace Initiatives

Ono’s activism extends to various other peace initiatives. In 1969, she and Lennon staged the “Bed-In for Peace,” a series of non-violent protests held in their hotel rooms in Amsterdam and Montreal. During these events, the couple invited the press to their bedside to discuss peace and non-violence, turning their private space into a public forum for activism.

Ono has also been involved in numerous humanitarian causes, supporting organizations that work towards nuclear disarmament, women’s rights, and environmental protection. Her ongoing support for these causes reflects her deep commitment to creating a more just and peaceful world.

Multimedia Art and Music

Ono’s Musical Journey

Ono’s artistic output extends beyond visual arts and performance into the realms of multimedia and music. Her experimental music, characterized by avant-garde techniques and unconventional structures, has influenced numerous musicians and artists. Albums like “Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band” (1970) and “Approximately Infinite Universe” (1973) showcase her innovative approach to sound and composition.

Ono’s musical journey began in the early 1960s, when she started collaborating with avant-garde musicians and composers in New York. Her early works, such as “Voice Piece for Soprano” (1961), explored the possibilities of the human voice as an instrument. This piece, which involves the performer screaming at the top of their lungs, challenges traditional notions of music and performance.

Influence on Music and Collaboration with John Lennon

Ono’s collaboration with John Lennon produced some of the most memorable music of the 20th century. Together, they pushed the boundaries of popular music, incorporating experimental elements and socially conscious lyrics. Songs like “Imagine” (1971) and “Give Peace a Chance” (1969) became anthems for the peace movement, reflecting the couple’s shared commitment to activism.

Ono’s solo work also stands out for its boldness and originality. Albums such as “Fly” (1971) and “Season of Glass” (1981) blend avant-garde techniques with rock and pop influences, creating a unique sonic landscape. Ono’s music often explores themes of feminism, identity, and social justice, using unconventional sounds and structures to challenge listeners’ expectations.

Legacy and Impact

Ono’s Enduring Influence

Yoko Ono’s legacy is multifaceted, encompassing significant contributions to art, music, and activism. Her work has inspired countless artists and activists, challenging them to think beyond conventional boundaries and engage with the world in transformative ways. Ono’s participatory art projects continue to resonate, offering audiences a platform to express themselves and connect with others.

Ono’s influence can be seen in the work of contemporary artists who embrace participatory and conceptual art practices. Her emphasis on audience engagement and collaboration has paved the way for new forms of artistic expression, breaking down the barriers between artist and viewer. Ono’s commitment to social justice and peace has also inspired a new generation of activists who use art as a tool for change.

Recognition and Awards

Despite initial criticism and controversy, Ono’s contributions have gained recognition over time. She has received numerous awards and honors, including the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement from the Venice Biennale in 2009. These accolades reflect her enduring influence and the growing appreciation for her work.

Ono’s recognition extends beyond the art world. She has been honored for her humanitarian efforts, receiving awards such as the Oskar Kokoschka Prize and the Hiroshima Art Prize. These honors acknowledge her contributions to promoting peace and social justice through her art and activism.

Conclusion

Yoko Ono’s powerful and participatory work stands as a testament to the transformative potential of art and activism. Her innovative approach to conceptual art, emphasis on audience engagement, and unwavering commitment to peace and social justice have left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape. As we continue to grapple with global challenges, Ono’s legacy serves as a reminder of the power of creativity and collective action in shaping a better world.

References

- Goldberg, R. (2004). Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present. Thames & Hudson.

- Hendricks, J. (1988). Fluxus Codex. Harry N. Abrams.

- Kotz, L. (2007). Words to Be Looked At: Language in 1960s Art. MIT Press.

- Ono, Y. (2000). Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings by Yoko Ono. Simon & Schuster.

- Sandler, I. (1998). Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the Early 1990s. HarperCollins.

- Yoshimoto, M. (2005). Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York. Rutgers University Press.

Leave a Reply