Last updated on September 9th, 2024 at 05:32 pm

Diplomacy has perpetuated China’s power disparity. The Qing dynasty (1644-1911) fiercely opposed Western photographers documenting the Second Opium War (1856-1860). After the Crimean Conflict, Western visual journalists experimented in China. In East Asia, the rapidly industrialising Japan saw the camera as a dreadnought battleship and used photography for imperialist aims. Photography outside of China may replace the traditional ways Chinese enjoy their cultural and material history.

Given photography’s revolutionary potential, ancient Chinese descriptions seem dated. Many commodities have a history of making new products look old and searching for indigenous roots. China’s first major photographer was Guangzhou mathematician Zou Boqi (1819-1869). He found that the camera followed optical concepts from 500 BCE literature.

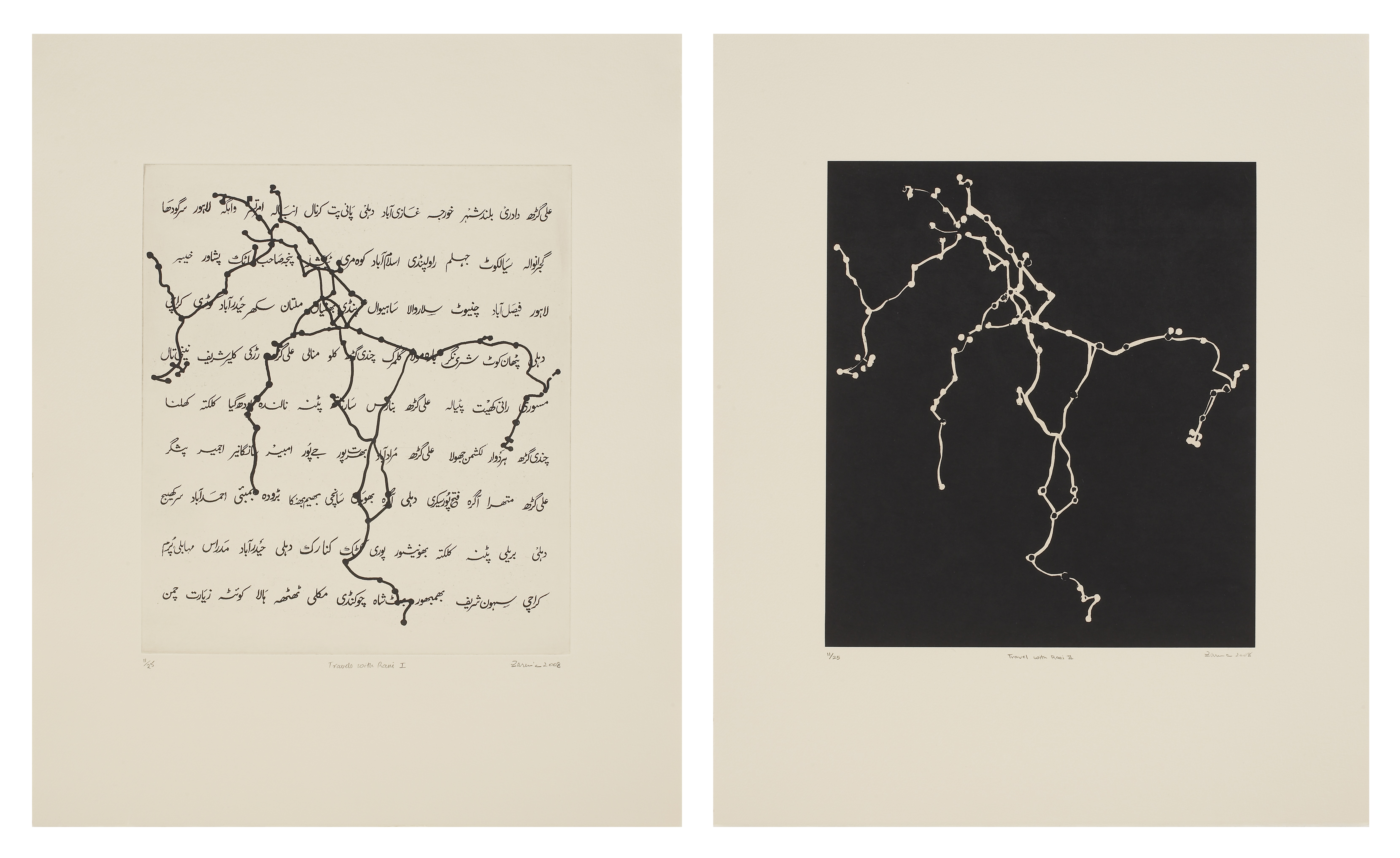

Photography was given numerous names, including “painting the verifiable image” (xiezhen), which is still used in Japan (as Shashin) but is archaic in China. The word’s Chinese painting philosophy etymology shows how often painting terms have been employed in photography discussions. Photography used monographic (hand-drawn) painting concepts. Photographers were traditionally thought to copy painters by calling their profession xiezhen. Importantly, relics show that photographers used terms from painting and woodblock printing to produce new works.

Studio system debate dominated Shanghai’s Lihua Studio on Nanjing East Road in 1890. This style of business is called “smarter” in advertising and other modern writing. Readers who had never heard of Zou Boqi were delightfully persuaded that photography was a Western method in early advertising. This ad shows photography familiarity. The new daily’s readers clearly understood photography’s technicalities. Western education adds legitimacy to the studio’s financial success and aesthetic insight, but readers must have a robust technical grasp.

This early studio advertisement shows the patron visiting the “artist” or photographer at the latter’s address, a social behaviour that emerged barely two decades before. A painter used to appear at a person’s door with a snap. Perhaps this social upheaval inspired the development of sumptuous studio premises, a “selling point” of many Shanghai advertising, to better accommodate consumers whose social status could otherwise limit their patronage. Other studios revealed new concerns. Even experimenting with morally problematic female portraiture might stress women.

Several researchers have noted the late 19th-century urban Chinese craze for photographic portraiture. Por-characteristic history and material culture are neglected. The regular advertising and even representation of all the required items for a stylish portrait—books, clocks, water pipes, paintings, furniture, official and theatrical clothes—is a fascinating document of supply and demand. Viewers could detect if a studio had the latest products by perusing the commercials. Thus, there was no need to buy all this equipment.

In portraits and landscapes, senior art traditions in photographs are noteworthy. An 1889 commercial shows landscape portraiture’s cultural and aesthetic value. Nanjing painter Qian Shouzhi focuses on landscape and people portraiture. Portraits cost $1, but elaborate backdrops cost extra. Qian made landscape fans of varied sizes and prices. This studio prices everything except the massive landscape backdrops that take the most time and work. He can choose from these as long as the client understands that different price points mean different service levels.

This is not a case of a new picture technology replacing an older one. Instead, it shows how a single operator used photography to repeat a variety of manugraphic visual creations in photographic form and earn various reproduction fees. Mr, Qian must justify his conservative visual nostalgia for his clientele with his roots in a Nanjing school of image training to make a life. Qian Shouzhi’s advertising is fascinating for studying modernity-tradition problems. One visual artist in Shanghai adopted new technologies to regain his economic edge as modern picture practises industrialised. By capitalising on the attractiveness of recent history and regional cultural standards, Nanjing, a city noted for elegance and brilliance in all forms of lyrical and visual innovation, further assured the social relevance of this strategy. On the other side, Qian Shouzhi’s image production purposefully mixed genres and made boundary-pushing a selling point, proving Weber’s theory that the market declassifies culture. However, his use of contemporary visual technology to place his art within the mainstream culture makes him seem like a shrewd salesman who knows which socially valued genres would succeed.

These studio ads show how photography and painting were considered ontologically comparable at the time. This allowed photography to be given the same artistic value as painting, as shown in current photographs and their reconfigurations.

The assumption that extremes of light and dark disfigured the subject was a major criticism of Chinese photography portraiture. Yao-Hua Studio responded with a double-airing 1896 ad after being criticised for providing excessively dark or light photos. The advertisement intends to show that these photos are Chinese-friendly because Yaohua had a German lighting specialist remodel its studio. Thus, the issue was not the rejection of European technology illumination in favour of Chinese aesthetics (photography is not adapted to that purpose).

Recent research questions photography’s Eurocentrism, its authors show how to see photography as a global and local art form. Chinese practitioners and consumers realised they had embraced Western visual technology. However, they improved visual products culturally by referencing established forms of art and illuminating the social settings that contributed to the image’s creator-viewer relationship. Photography needs a language apart from advertising. These texts assist readers in understanding the cultural norms and values of late nineteenth-century Shanghai and place visual images in their right historical and cultural context. Shanghai and Chinese photography combined new substance and form with new social habits. Ads weren’t only reports that started change and were visualised afterwards but also signals of societal transformations.

Leave a Reply