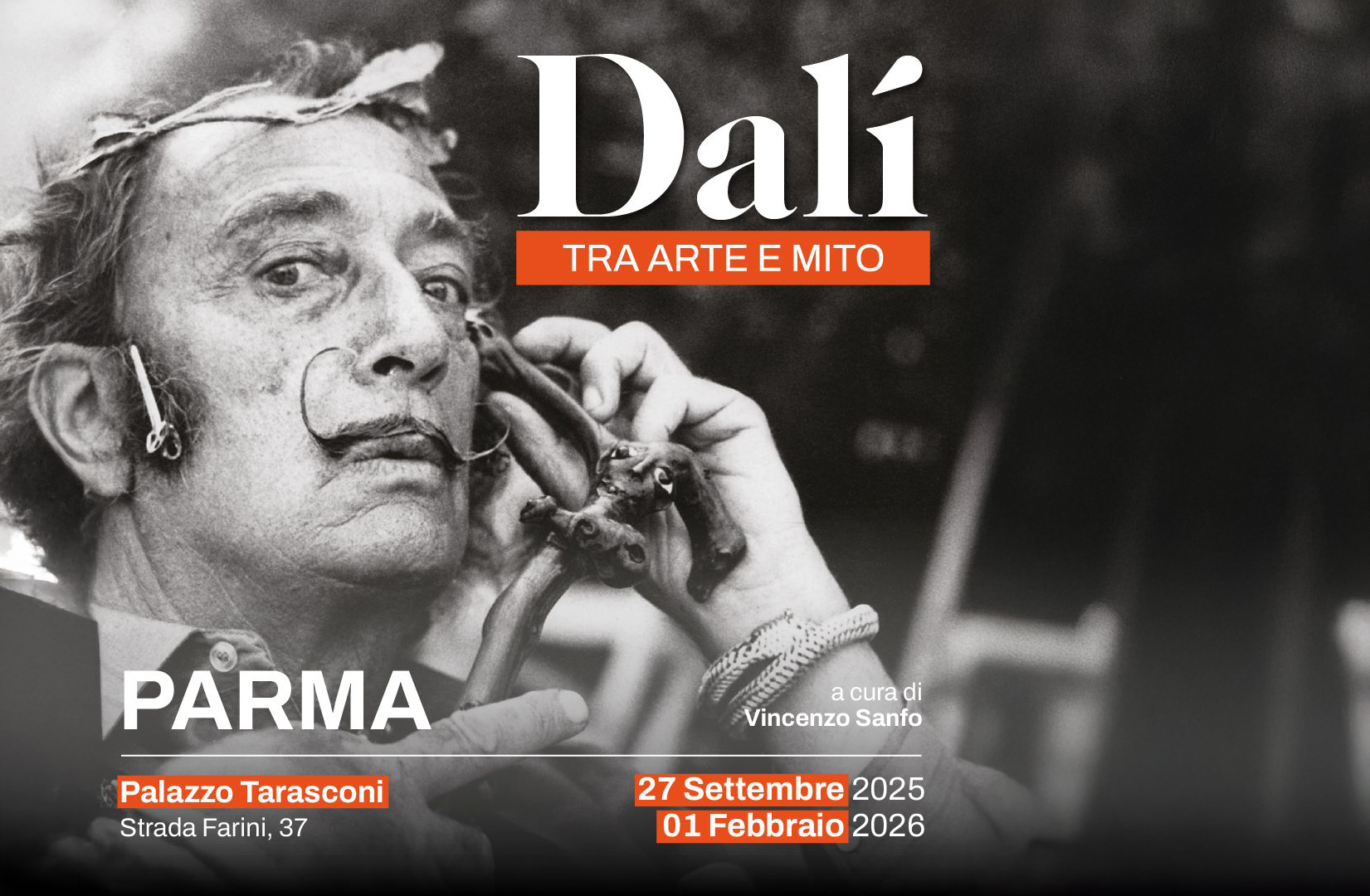

PARMA, Italy— Italy’s elite art crime unit has taken 21 works of art from a major exhibition that were said to be by Salvador Dalí and claimed they were sophisticated forgeries. This has sent shockwaves through the international art community. The dramatic raid on October 1, 2025, at the famous Palazzo Tarasconi in Parma, was aimed at the newly opened exhibition “Dalí, Between Art and Myth.”

The exhibition “Dalí, Between Art and Myth” has turned a well-known cultural event into the center of a huge, nine-month investigation. The seizure of the works—a collection of drawings, engravings, and tapestries—has put a lot of pressure on the people who put on the show, the private lenders who lent the art, and the weaknesses that are often hidden in the world of touring art shows.

The Comando Carabinieri per la Tutela del Patrimonio Culturale (TPC) carried out the operation, which was not a random act but the result of a careful investigation that began months earlier in Rome with the keen eye of a single officer. This case is a clear reminder of how common and profitable art forgery is, especially for an artist as famous and complicated as Salvador Dalí. His own controversial actions decades ago unknowingly set the stage for the fraud that now threatens his legacy.

The Detailed Look into the Dalí Show

The seizure at Palazzo Tarasconi didn’t start with a tip-off; it started with expert intuition. In January 2025, Senior Officer Diego Poglio of the Carabinieri TPC was doing a routine check on the exhibition’s first stop at the Museo Storico della Fanteria (Historical Museum of the Infantry) in Rome when he thought, “Something seemed to be wrong.” His suspicion came from something strange in the way things were curated and the way money worked.

Officer Poglio told The Guardian, “We saw that only lithographs, posters, and drawings by Dalí were on display, along with a few statues and other things, but no paintings or anything else important.” “It was difficult to see why someone would want to put on a show of such low-value works.” This important observation, which was more like what a market analyst would do than what a police officer would do, started the investigation.

The next thing the Carabinieri did was crucial. They got in touch with the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí in Figueres, Spain. This corporation is the official group that the artist set up to protect his legacy. The Foundation’s response was quick and scary: they had never heard from the people who put on the exhibition. “We found the situation very strange,” Poglio said, “because if you want to put on an exhibition of an artist’s works, especially a big one, you have to go through the foundation that manages the collection.”

This serious violation of protocol made the Carabinieri’s suspicions even stronger. They sent the exhibition catalog to the Foundation for an expert review in February 2025. The Foundation released an official report the next month that said they were “strongly perplexed” about the origins of many works, singling out “three drawings and a series of prints” as being very questionable. The Foundation sent its experts to Rome to confirm their findings. After looking at the situation in person, they confirmed that there were “ambiguities” that needed official action.

The Carabinieri took their case to the Rome Public Prosecutor’s Office with this expert testimony. The evidence was strong enough for magistrates to ask for a seizure order, which a judge granted. Authorities waited for the exhibition to finish its six-month run in Rome (from January 25 to July 27) and move on to its next location as part of a plan. The TPC carried out the warrant just days after the show opened in Parma on September 27. They took 21 specific works, including 18 lithographs and three drawings. Since then, investigators have linked these items to loans from only two private Italian citizens, which has greatly narrowed the scope of their ongoing investigation.

The Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation’s Important Role

The Parma investigation shows how powerful artist-endowed foundations are in the modern art world. The Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, which the artist started in 1983, is the only organization that can “promote, foster, disseminate, enhance, and defend Dalí’s world worldwide” and verify the authenticity of his work. Italian police called the warning it gave to the Carabinieri “decisive.”

It is especially bad that the organizers didn’t get in touch with the Foundation, given how complicated Dalí’s market is. The Foundation’s official website says that its Authentication and Cataloguing Commission provides formal expert services for unique works like paintings and drawings. However, it does not offer this service to the public for graphic and three-dimensional works, which were the majority of the art that was seized.

People who want to get around strict verification can take advantage of this policy’s gray area. An organizer might say that there is no need for consultation because there is no public certificate for prints. The Parma case proves that argument wrong. The Foundation may not give out public certificates for prints, but its response to the Carabinieri shows that it has the deep institutional knowledge to spot likely forgeries and will give law enforcement important information to protect the artist’s legacy. The people in charge made a big mistake by not getting a certificate that isn’t available. They should have asked the first, most basic question that is standard practice in their field.

Examination of the Dalí Exhibition Organizers and Venues

Navigare srl, a company in Palermo that specializes in touring exhibitions, put on “Dalí, Between Art and Myth” as a business. The show was billed as a complete look at Dalí’s world, with 80 to 120 works from private collections in Italy, Belgium, and France. It was put together by international curator Vincenzo Sanfo.

Navigare has already felt the effects of the seizure. The investigation made the company put off a different photography show about Frida Kahlo that was supposed to happen in Milan. At first, Navigare promised to fully cooperate with the authorities. But later, the company’s lawyer, Fabiola Lacagnina, took a more defensive tone and said that Navigare had “suffered a damage of image” and would take legal action against anyone found to be responsible. She said the company had “acted in regola” (followed the rules), which is very different from what the Dalí Foundation said, which was that they were never contacted.

The host venues, Rome’s Museo Storico della Fanteria and Parma’s historic Palazzo Tarasconi, have also been affected by the scandal, which has hurt their credibility as institutions. Even though the 21 pieces were taken, both the organizers and the Parma ticket office said the show would go on without them. This business decision raises moral questions about the integrity of the rest of the collection.

The Ongoing Issue of Fake Dalí Art

Salvador Dalí is often listed as one of the most forged artists in the world, along with Picasso and Modigliani. This isn’t just because he’s famous; it’s because of what he’s done. André Breton, a Surrealist who lived at the same time as Dalí, famously came up with the anagram “Avida Dollars” to criticize Dalí’s constant need for money.

Starting in the 1960s, he signed thousands of blank sheets of lithograph paper, which hurt his own legacy the most. Dalí was said to be able to sign up to 1,800 sheets an hour because he wanted quick cash. This flood of pre-signed paper permanently ruined his print market, making it a “perfect storm” for forgers. It gave dishonest dealers a good excuse, since they could say that any print with a fake signature was made on one of the real pre-signed sheets. The rumor about the signed sheets grew stronger than the sheets themselves, making it possible for many forgeries to be made to meet high public demand. Experts all agree that Dalí did not sign any prints after 1980, but by then the damage had already been done, and there were too many questionable works on the market.

Authenticating Dalí: A Difficult Mix of Science and Art

Because of this complicated history, it is hard to prove that a Dalí work, especially a print, is real. Experts use three things to prove that something is real: its history, its quality, and scientific study.

First and foremost is provenance, which is the written record of who owns something. The Dalí Foundation was “strongly perplexed” about the works in Parma because their provenance was questionable, which is a big red flag for any expert. Second is

Connoisseurship is the expert’s trained eye for things like stylistic quality, signature variations, and the presence of real publisher’s marks and correct editioning. Lastly,

Scientific analysis provides us objective information. FFor prints, this involves examining the watermarks on the paper. After 1980, the mills that made Dalí’s paper added an infinity symbol (∞), so any print with both a signature and that watermark is definitely a fake. Experts also use magnification to tell the difference between original printing methods and photomechanical reproductions. We will now use these methods on the 21 pieces that were taken, along with the complete catalogue raisonné of his graphic works.

The Dalí Seizure Shows a Systemic Failure in the Art World

The seizure in Parma is not just an isolated event; it is a case study of the risks that exist in the global art market. Officer Poglio said that the “significant presence of fakes in the market… is a global phenomenon.” The Carabinieri have recently broken up a number of large forgery networks, but the problem is still there. One institute estimates that more than half of the art in circulation may be fake or misattributed.

Ironically, public exhibitions are often the first places where experts look closely at these fakes. This puts a huge amount of responsibility on the people in charge. Poglio said, “Many of those behind the exhibitions act in good faith,” but he gave a stern warning: “Those in charge of the scientific curation must always conduct thorough checks on authenticity before displaying the works.”

The investigation is still going on, and Italy’s Culture Ministry is now using science to look at the 21 works. If they are proven to be fake, they will be taken away for good, and prosecutors will try to hold the lenders and organizers responsible for their actions. No matter what the law says, this case has set a new, clear standard of care. If an institution wants to show the work of a famous artist, it is very careless to skip the official artist foundation. The seizure of art in Parma is a strong public lesson that in the strange world of the art market, careful research is the only way to protect cultural integrity and the public’s trust.

Leave a Reply