The news on June 24, 2025, that Angela Harutyunyan and Paula Nascimento had been appointed curators of Sharjah Biennial 17 was far more than just a standard update to the calendar of world art. For one of the most important large-scale shows in the world, it was a well-crafted intellectual proposition—a declaration of intent that marks a dramatic change. The Foundation has created a dialogue of immense critical urgency by matching a leading theorist of post-Soviet temporality with a pioneering architect-curator of the urban fabric of the Global South. This alliance is more than just a cooperation; it’s a convergence of two strong analytical models ready to probe the very spatial and temporal politics defining our modern reality.

Particularly since its major reorientation in 2003 under the direction of Hoor Al Qasimi, the Sharjah Biennial‘s path has been one of constant and increasing critical investigation. From a nationally representative model to a curator-led, research-driven platform, it has evolved to play a unique and indispensable role as a site for “creative experimentation, collaboration and social impact.” For artists and intellectuals from the Global South, it serves as a vital stage and an intellectual anchor in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia (MENASA). Al Qasimi’s declared vision for the 2027 edition—to create a “space for critical engagement and collective reflection, where their curatorial visions can cooperatively explore new contemporary realities”—underscores the deliberate character of this appointment. The choice of Harutyunyan and Nascimento makes it abundantly evident that Sharjah Biennial 17 (SB17) will go beyond a simple exhibition of global art to engage in a structural study of the planet that art inhabits.

This curatorial alliance promises a biennial that questions the afterlives of the grand ideological projects of the twentieth century—colonialism and state socialism—and looks at how their ruins remain within the material and psychic infrastructure of the present. It points to a show examining the temporal dissonances and spatial logics of a society negotiating its post-ideological state. The curators of Sharjah Biennial 17 are positioned not only to plan an exhibition but also to create a strong analytical lens through which to view our global contemporaneity by combining these two quite different but profoundly complimentary points of view.

Examining Angela Harutyunyan’s curatorial grammar: the archaeologist of afterlives

One must go beyond Angela Harutyunyan’s curatorial projects to grasp the intellectual weight she brings to Sharjah Biennial 17 through her scholarly work. Her work is that of an intellectual archaeologist, excavating the layered political aesthetics and temporalities that afflict the post-Soviet terrain. Her whole intellectual path, molded by a life across geopolitical boundaries, has readied her for this work. Born in Gyumri, Armenia, in 1982, Harutyunyan’s academic and professional path has taken her from the former Soviet sphere to important intellectual hubs in the Middle East, including the American University in Cairo and the American University of Beirut, and now to a professorship in Contemporary Art and Theory at the Berlin University of the Arts. The book is a living experience of the very transnational intellectual currents and geopolitical “margins” she studies, not a casual biography. It gives her a unique vantage point from which to question hegemonic Western art historical narratives, so augmenting an important academic journal she co-founded to link art histories from outside dominant Anglo-American circuits.

Thinking the Undead: Post-Socialism and Historical Temporalism

Harutyunyan’s outstanding scholarship offers a straight key to her curatorial vision. Her first English-language study of modern art in Armenia and a vital case study in how art negotiates periods of significant political transformation is her foundational book, The Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-garde: The Journey of the ‘Painterly Real,’ 1987–2004. She painstakingly charts in it the development of modern art in Armenia from within and in opposition to the institutional and aesthetic legacies of Socialist Realism and National Modernism, following a complex dialectic of rupture and continuity with the Soviet past. This work reveals her central passion in how artistic forms register the seismic changes of political and ideological collapse.

Her more recent work on what she defines as “historical presentism” culminates this passion. Presentism, as the materials for a course she teaches define it, is an ideologically imposed condition hegemonic in our modern era, “marked by the omnipresence of the present, without a sense of a historical past or futurity.” Born in her analysis from the failure of twentieth-century revolutionary projects, it is a temporal logic born from the flattening, perpetual “now” controlled by the deadlines of neoliberal capital and the approaching threat of ecological catastrophe. This theoretical framework is not only intellectual; it’s the main diagnostic tool she uses for our cultural moment and directly highlights her curatorial statement for SB17.

Harutyunyan is advocating a direct curatorial confrontation with historical presentism when she expresses her interest in looking at “the ways in which artworks encapsulate and figurate decaying but undead afterlives of the emancipatory projects of non-capitalist modernity.” The “undead afterlives” are the spectral remains of failed socialist and other utopian projects that refuse to vanish totally. As she has argued elsewhere, they are the “zombies or ghosts” of a revolutionary past haunting the smooth narrative of the neoliberal present. She wants to test her own “possibilities and limitations… in making visible the uneven temporal rhythms that pulsate beneath contemporaneity” using the biennial form. For Harutyunyan, art becomes a vehicle for temporal insurgency—a means to show the non-linear, asynchronous, ghostly persistence of history against the “homogeneous empty time” of the present. This approach fits her with a wide constellation of post-socialist artists who struggle with memory, trauma, and the complicated legacy of failed ideas, including Ilya Kabakov, Marina Abramović, and Boris Mikhailov.

Organizing as a Critical Intervention

Past curative work by Harutyunyan shows a constant application of these theoretical issues. The 2014 show is This Is the Time. Co-curated with Nat Muller, this Record of the Time drew inspiration from a Laurie Anderson song capturing a sense of approaching catastrophe and loss of control. The idea of the exhibition challenged whether our modern systems of recording—social media, constant news feeds—truly help us understand our times or simply overload us with information, activating different temporalities to demand a pause and contemplation. Her ongoing fascination with temporality as both a topic and a medium of curatorial work is obviously modeled by this project.

Her attitude to teamwork also stems from a critical awareness of the curator’s responsibility. She has argued for a practice of facilitation and dialogue—an “intermediation of relations”—instead of the curator’s model as a single author pursuing self-representation. Her natural fit for a co-curated biennial comes from this ethos, which also suggests a fundamentally dialogic process for SB17 that will be not only in its final form but also in its very method of creation.

Geopolitics of Form: Expanded Infrastructure Designed by Paula Nascimento

Paula Nascimento’s practice is anchored in the material and spatial reality of the Global South; Angela Harutyunyan’s is based in the excavation of temporal and ideological layers. Her work as an architect and independent curator from Luanda, Angola, provides a potent “bottom-up” analysis derived from the physical circumstances of post-colonial urbanism, geopolitics, and arts education. Her method is reading the site itself—its buildings, voids, and flows of people and money—as a complex geopolitical text, not about applying pre-existing theory to a site.

A Viewpoint of the Global South from an Architect

Still the Angolan Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013, Nascimento co-curated and won the coveted Golden Lion for best national participation—a first for an African country. The show, “Luanda, Encyclopedic City,” included Edson Chagas’ “Found Not Taken” photographic series. Beyond only presenting images, the project was a masterful curatorial intervention. The images, which captured discarded items on the streets of Luanda, were presented not as framed artworks on a wall but as stacks of posters on pallets, free for visitors to take. This one action masterfully challenged the basic Western museum and art market logic: collection, scarcity, financial value, and archive permanency. The artwork’s value was shared and remade with each guest who took a piece home. Enacting spatial and material means, it was a curatorial idea meant to be a significant statement on consumption, value, and the very nature of an encyclopedic project in a post-colonial setting.

Beyond Entropy: Theory of Metamorphic Space

Beyond Entropy Africa, a research-based studio he co-founded with Stefano Rabolli Pansera, offers the intellectual framework for the Venice pavilion and much of Nascimento’s work. Operating at the junction of art, architecture, and geopolitics, Beyond Entropy uses the concept of “energy” not in a merely technical sense but as a lens to “conceive new architectural strategies that reveal space not as a fixed, measurable entity but as a temporal coalescence of continuously unfolding forces.”

From this, Nascimento created the important idea of “metamorphic space” to characterize the real state of many African cities. In cities like Luanda, which lack official infrastructure and have high population density, a single space is rarely set aside for one use. A house is also a shop, an office, and a garage; a street is also a social forum and marketplace. Born from need and adaptation, this observation of spatial fluidity and multifunctionality turns into a potent theoretical instrument. It implies that value and meaning are constantly generated and repeated by use, not natural features of buildings. The argument connects her work to a larger conversation among African artists and thinkers like El Anatsui and Ibrahim Mahama, who engage with urbanism, infrastructure, and repurposed materials to criticize global economic systems and environmental challenges. Her Venice pavilion’s ethos speaks to these issues deeply.

Curating as “Geopolitical Exercise” and “Expanded Infrastructure”

Nascimento herself has characterized her curatorial approach as a “geopolitical exercise,” a framework clearly seen in her considerable work throughout the continent and the Global South. For the sixth and seventh editions of the Lubumbashi Biennial, for example, she worked with themes like “ToxiCité,” which specifically linked the post-colonial urban setting to the material consequences of industrial and ecological toxicity—a condition of life impacting social worlds in Lubumbashi and the larger urban Global South. She was an associate curator for both editions.

Her declared interest in SB17—”thinking with artists and in the articulations between artmaking and infrastructure in an expanded way”—results directly from this viewpoint. Her architectural and curatorial approaches are crucially connected by the idea of “expanded infrastructure.” Infrastructure—physical, social, financial, or institutional—is not a neutral container for art for Nascimento; rather, it is a politically charged system to be read, questioned, and maybe rebuilt. According to an “expanded” perspective, the whole biennial apparatus—its exhibition sites, funding sources, discursive platforms, and social networks—forms one cohesive infrastructure. The artist and curator’s job then is to activate this system, expose its hidden logics, and investigate art’s “capacity to imagine and propose spaces and other worlds and forms of relations.” This is a very political and structural approach to the act of selecting.

A Dialogue of Souths: Theorizing the Sharjah Biennial 17 Trajectory

Angela Harutyunyan and Paula Nascimento’s appointment is not only the result of two outstanding people but also of intentional staging of an intellectual conversation. Working together as Sharjah Biennial 17 curators promises a synthetic vision that might redefine the possibilities of the biennial form. SB17 is ready to present a multi-layered critique of our global situation by combining Harutyunyan’s deep analysis of temporal politics with Nascimento’s grounded approach to spatial geopolitics.

Fundamentally, the collaboration finds common ground in a shared concern with the “afterlives” of twentieth-century modernism. While Nascimento studies the material and social legacies of colonialism in the Global South, Harutyunyan looks at the spectral persistence of failed socialist utopias in the post-Soviet world. Both are essentially interacting with societies negotiating the wreckage of big ideological projects against an ascendant, apparently monolithic neoliberal globalization. This common interest in post-ideological environments offers a strong basis for joint research.

Productive Frictions: Time in the Structure and Ghosts in the Machine

The real power of this curatorial pair is found in the creative friction between their different but complimentary approaches. Temporal and ideological, Harutyunyan asks, “What ideological ghosts haunt this present moment? What are the ‘undead afterlives’ of past emancipatory projects? She is especially interested in the psychic and political systems of time itself. By contrast, Nascimento’s lens is material and spatial. She probes, “How is this present moment physically constructed? What are the politics embedded in its infrastructures, both visible and invisible?”

These questions taken together form a strong dialectic. SB17 can commission and frame artwork examining how physically ingrained historical tragedies and failed utopias—Harutyunyan’s ghosts—are within the buildings, urban plans, and logistical networks—Nascimento’s structures—that mold our planet. An artwork might investigate, for example, how the architecture of a public square captures the memory of a political struggle or how the “metamorphic” use of space in an informal settlement responds directly to the shortcomings of colonial-era urban design. Such an investigation produces a curatorial framework capable of exposing the invisible ideological forces animating our built environment, simultaneously highly theoretical and materially grounded.

Combining a curatorial vision toward a heterogeneous South

This cooperation also sets up a vital conversation between two different but connected geopolitical “Souths”: the post-Soviet “East” and the post-colonial “Global South.” This action subtly questions the sometimes-monolithic and over-generalized use of the term “Global South” in modern art debate. The Harutyunyan-Nascimento alliance allows for a more complex, comparative study of many post-imperial conditions rather than supporting a simple binary between a hegemonic “North” and a united “South.”

SB17 can thus become a venue for investigating the common and unique experiences of societies rising from many kinds of empire and modernity. It can inquire about how Soviet internationalism differs from the legacy of European colonialism and what it has in common with This strategy fits a more complex and critical view of global peripheries as a “homogeneous South,” which acknowledges the unique and particular histories linking and separating areas outside the North-South axis. Engaging the cutting edge of postcolonial and decolonial theory, this highly advanced curatorial proposition interacts with Eurocentric frameworks and calls for South-South dialogues increasingly.

The Curatorial Model as Political Exercise

At last, the very decision to take on a co-curatorial model is a political statement. In an art world sometimes dominated by the figure of the singular “celebrity” curator, this cooperative appointment reflects a dedication to a more dialogic, negotiated, and multidisciplinary process. It fits modern “curatorial activism” and group projects aimed at subverting hierarchical systems and promoting mutual support. Combining an architect-practitioner rooted in material reality with a theorist known for her thorough historical analysis creates a model of knowledge production that crosses theory and practice, thought and action. This cooperative attitude is fundamental to the biennial’s critical approach rather than only a management tool.

Setting the scene for Sharjah Biennial 17’s curators

Angela Harutyunyan and Paula Nascimento’s appointment is not a one-off occurrence but rather a logical and aspirational turn in the development of the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF). Their particular intellectual projects find a particularly fitting and strong setting in Sharjah, a city molded by a consistent vision and a unique material environment.

The Institutional Vision of Hoor Al Qasimi

Hoor Al Qasimi has been the catalyst behind the Biennial’s evolution from a regional, pavilion-based event into one of the most esteemed venues for critical contemporary art since assuming leadership in 2003. Deeply inspired by the innovative postcolonial curatorial practice of the late Okwui Enwezor, her vision has regularly focused the Biennial as a site for research, experimentation, and dialogue outside of dominant Western institutional models. Sharjah Biennial 15 was conceived by Enwezor personally.

Thinking historically in the present—which Al Qasimi selected following his death—is the most powerful and direct guide for SB17’s orientation. That edition confirmed the Biennial’s dedication to investigating postcolonial subjectivity, transgenerational memory, and global modernism, so establishing the intellectual foundation for Harutyunyan and Nascimento’s work. Al Qasimi has developed an institutional culture at SAF that supports artists from the Gulf region and the wider Global South, transforming underused areas into centers of creative innovation and so promoting a patient, long-term cultural impact.

Sharjah as a conceptual and material site

For this particular curatorial team, the Sharjah Biennial’s physical surroundings offer a perfect laboratory. The Biennial is well-known for using historic sites—which are woven into the emirate’s metropolitan fabric—that have been repurposed. Venues are former souqs, restored historical buildings, modernist architectural icons like The Flying Saucer, and decommissioned industrial sites including the Kalba Ice Factory and the Al-Qasimiya School; they are not neutral white cubes.

Here, the theories of Harutyunyan and Nascimento can be powerfully realized in architecture. These buildings are the actual tangible proof of the “afterlives” Harutyunyan investigates. A 1970s clinic converted for use as a gallery is more than just a venue for art; it’s a site rife with memories of public health campaigns, modernization programs, and social change. The Al Mureijah Square restored heritage buildings are physical links to a pre-oil economy and way of life. These places are the very “infrastructure” Nascimento questions. Sharjah’s physical surroundings let the curators stage a direct encounter between modern art and the material ghosts of the past, transcending representation. The site thus becomes a dynamic participant in the curatorial concept, offering a rich, textured ground for examining the interaction of time, memory, space, and power.

The Biennial’s Part in the MENA Art Ecosystem and Beyond

Within the larger framework of the Gulf region’s rapid cultural growth, the Sharjah Biennial holds a particular place. While surrounding emirates have concentrated on creating commercially driven art fairs and big, franchise-style museums, Sharjah has developed a reputation as an intellectual and experimental center. It provides a critical counterpoint, giving research top priority, commissioning fresh work top importance, and encouraging conversation that questions accepted wisdom.

This is not to argue the Biennial runs outside the objectives of national development and cultural diplomacy for the UAE. It is, like all significant cultural establishments in the area, a tool for soft power and nation branding. Sharjah’s unique approach, however, is to create its worldwide influence by producing rigorous, critical knowledge rather than by relying just on spectacle. The Sharjah Biennial has grown to be a globally important event that provides a forum for difficult dialogues on post-colonialism, decoloniality, and the legacies of modernity, attracting artists, curators, and intellectuals who seek a depth of involvement rare in the biennial scene.

Towards a Critical Re-orientation Biennial

In the field of international contemporary art events, the appointment of Angela Harutyunyan and Paula Nascimento as Sharjah Biennial 17 curators marks a historic occasion. It offers a curatorial vision of extraordinary intellectual ambition, combining a visionary architect of spatiality and post-colonial geopolitics with a great theorist of temporality and post-socialist memory. This cooperation is synthetic, meant to probe the basic structures—material, ideological, social, and temporal—that define our global condition, not only the sum of its components.

Their combined strategy promises a biennial that transcends the celebratory presentation of art from many locations. Rather, SB-17 is about to undergo a critical reorientation. It will probably question the very form of the biennial itself, using it as an “expanded infrastructure” to probe the “uneven temporal rhythms” hiding under the surface of our rapidly changing present. Through a dialogue between the afterlives of colonialism and state socialism, the curators hope to create a more complex, “homogeneous” knowledge of the Global South, transcending simple binaries and moving toward a sophisticated appreciation of linked, but different, historical paths.

The intellectual project suggested by Harutyunyan and Nascimento is not only relevant but also essential in a society marked by a constant present and shaped by often invisible logics of global capital. Their work promises a biennial that is not only about what art is but also about what art does: how it can make visible the ghosts of the past, how it can reconfigure our understanding of space, and how it might suggest “other worlds and forms of relations.”

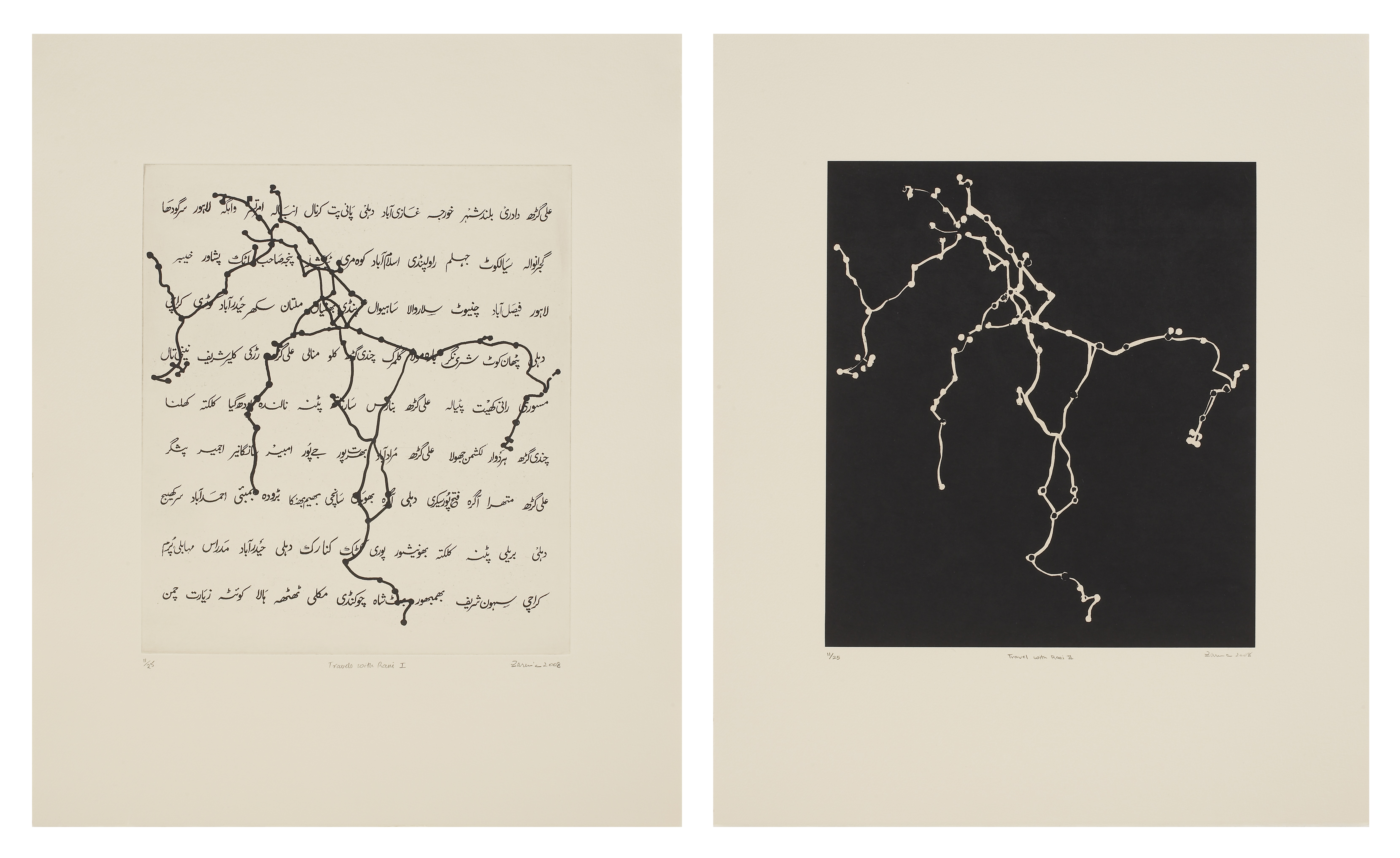

All images courtesy of the Sharjah Art Foundation

Leave a Reply